A light fog surrounds the group as dawn breaks and they set out on their trip. The party consists of twelve individuals, including various adults, children, and tiny tots who must be carried by the females in the group.

This is one of the human groups that frequented the Pyrenean Mountains during the period known as the Last Glacial Maximum, or

Ice Age

. These

Homo sapiens

– nomadic hunter-gatherers who populated Western Europe between 11,000 and 35,000 years ago – carry with them a leather rucksack containing objects of value: mostly

flint

cores and flakes that they will use on the journey as hunting tools, or as ornaments. These are pieces of their homeland.

By mid-morning, the group arrives at their destination for the next few days: the wide Pyrenean valley of Cerdanya, one of the enclaves that, generation after generation, has served as both a refuge and meeting place.

Today, this location is called Montlleó; it is a Magdalenian-era open-air archaeological site situated at a high elevation in Catalonia.

Pyrenees

. At around 1,144 metres above sea level, in the Coll de Saig, it is one of the most favourable mountain passes for crossing the Pyrenees. Even during the Ice Age, when glaciers covered much of the landscape, Cerdanya was still passable.

They plan to stay for several days, maybe hunting a horse or a goat and interacting with neighboring groups. These neighbors hail from either side of the mountain range and follow similar customs. During their gatherings, they discuss their experiences as well as trade thoughts, items, and resources.

Some groups come from the coast, bringing with them an abundance of perforated seashells which adorn their necks and clothing. Others bring small, high-quality flints that they exchange for resources such as deer or reindeer antlers.

On the first night, they show the projectiles they have made. These objects all have the same purpose: to wound an animal until it dies and becomes food for the group. However, each object is characteristic of its community, made with different varieties of flint and in a particular shape. They are, in a way, a distinctive element of each clan, similar to the tradition shared by the different communities that frequent the Pyrenees.

Mapping prehistoric movements

The archaeological research carried out in recent decades has allowed us to travel back in time in order to complete, little by little, the puzzle that is the study of prehistory.

Archaeological work in the Pyrenees has shown that human populations adapted to changes in the mountain environment and settled in areas that had initially been considered permafrost: permanently frozen ground during the Last Glacial Maximum.

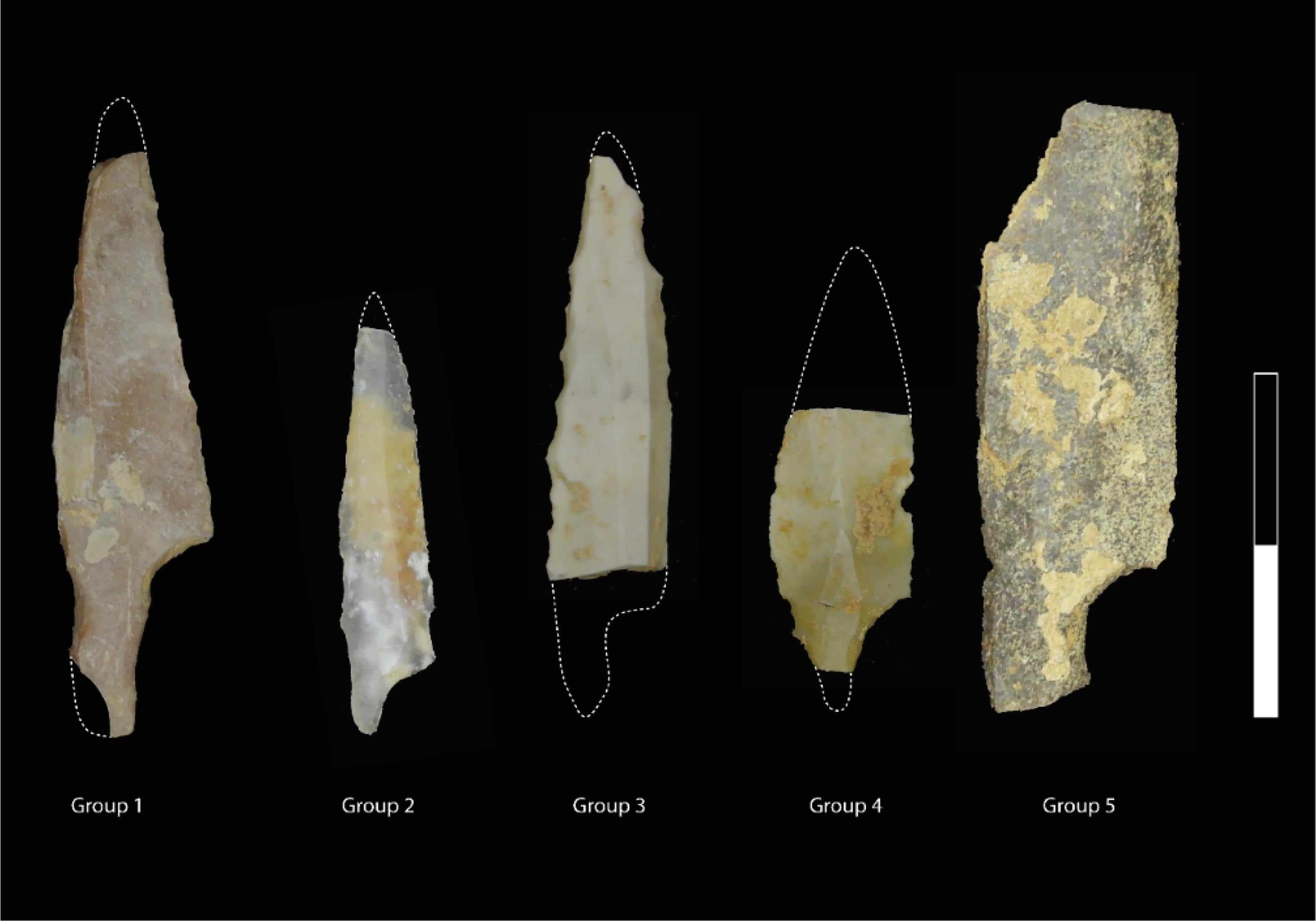

To find out how and where these groups moved in the Pyrenees, we can study the valuable tools and ornaments that they carried with them from their place of origin. The lithic industry discovered at Montlleó is made up of more than 25,000 pieces, of which more than 2,000 are finished flint tools and cores (masses of homogeneous rock that are carved to extract flakes for later use). We have a good number of objects to trace.

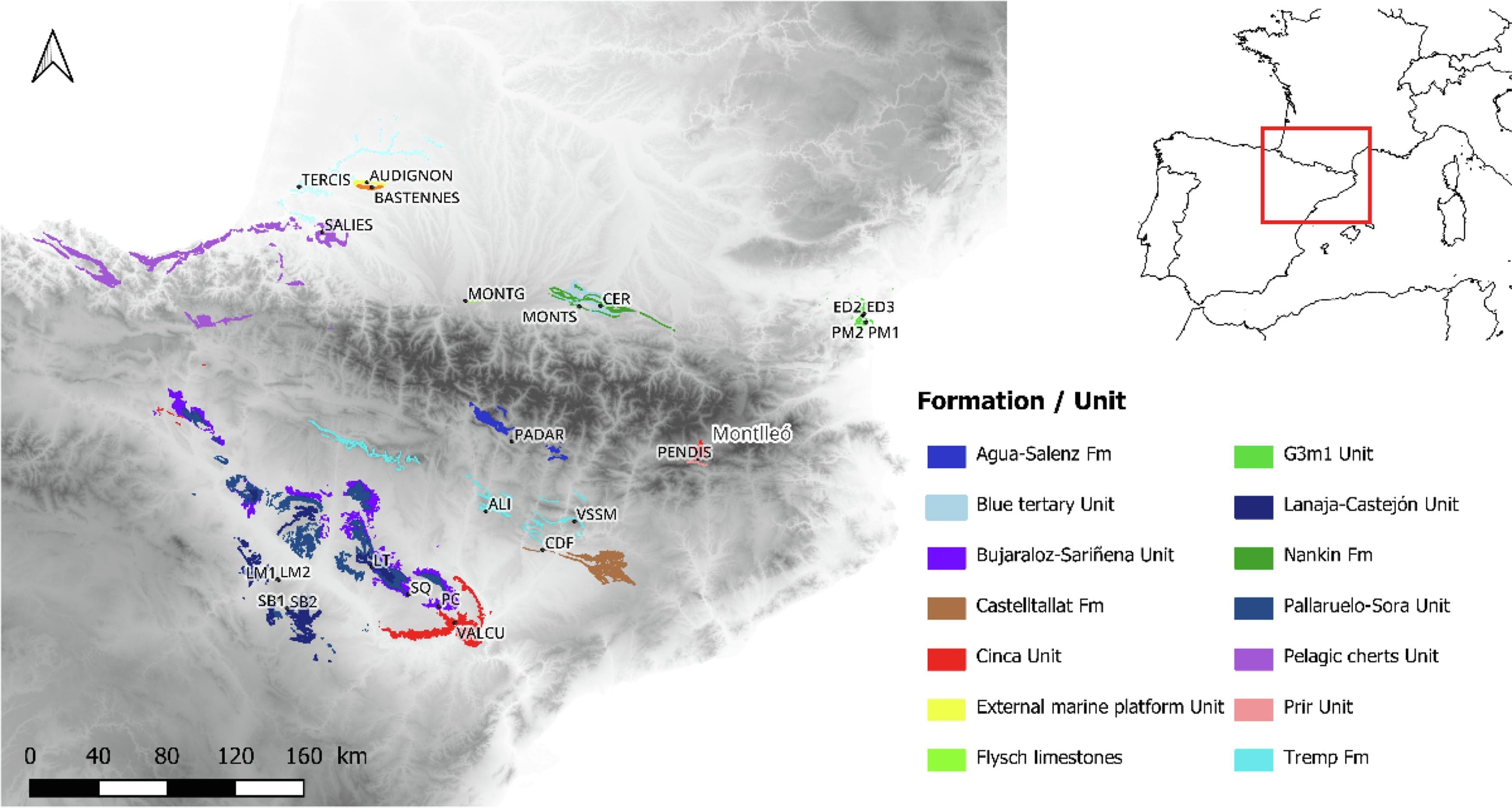

Our research project – named SPEGEOCHERT and funded by the

European Research Council

(ERC) – traces the routes followed by human groups to cross the Pyrenees. Today we know that the mountains were not a barrier, but rather a passage frequented by the

Homo sapiens

of the Upper Palaeolithic.

Among the project’s many surprises, three specimens of possible flint from Chalosse have been tentatively identified. They are from the south-west of present-day France and represent, for the time being, the most distant source.

Favourite flints

To outline these possible paths, we depended heavily on an extensively documented element from the archaeological record: flint tools, which were among the most commonly utilized materials during prehistoric eras.

The properties of flint are distinct to where and when it formed within the Earth’s geological timeline. This enables us to determine, through thorough examination, the source of artifacts discovered in the archaeological record.

Our group is striving to identify and retrieve specimens from rock layers that contain chert akin to what has been discovered at ancient archaeological spots. During our investigation, we’ve observed that various types of cherts do not cover the same geographical area. This suggests that certain “preferred” varieties may have been more widely traded or utilized than others.

In our study, we chose specific varieties of flint as indicators or signposts. Through monitoring how far they spread outwards from their origin point, we could trace the movement patterns of the communities transporting them. These categories encompassed compact core samples tailored for engraving purposes along with rudimentary implements like cutting edges and splinters, alongside fully formed instruments poised for immediate application.

We examined the archaeological flint tools gathered from over 20 sites across the Pyrenees Mountains, as well as reference specimens sourced from different geological strata, at multiple scales.

Geochemical analysis subsequently enabled us to identify a connection between the archaeological artifact and the original source region.

Finally, we utilized Geographic Information Systems (GIS), incorporating various factors like terrain features and dominant weather patterns. Using this approach, we propose potential paths these groups might have taken to obtain flint. In essence, this helps us understand their movement and interaction with mountainous regions.

It is now acknowledged that at least two primary natural pathways for traversing the Pyrenees were utilized by ancient human communities: the “Basque Crossroads” in the western region and the Cerdanya Valley in the eastern part. This indicates that humans inhabited high-elevation open spaces during the Ice Age as more than just a theoretical concept; it was indeed an established fact.

Marta Sánchez de la Torre is an associate professor of Prehistory at the University of Barcelona.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the

original article

.

The Independent has always had a global perspective. Built on a firm foundation of superb international reporting and analysis, The Independent now enjoys a reach that was inconceivable when it was launched as an upstart player in the British news industry. For the first time since the end of the Second World War, and across the world, pluralism, reason, a progressive and humanitarian agenda, and internationalism – Independent values – are under threat. Yet we, The Independent, continue to grow.